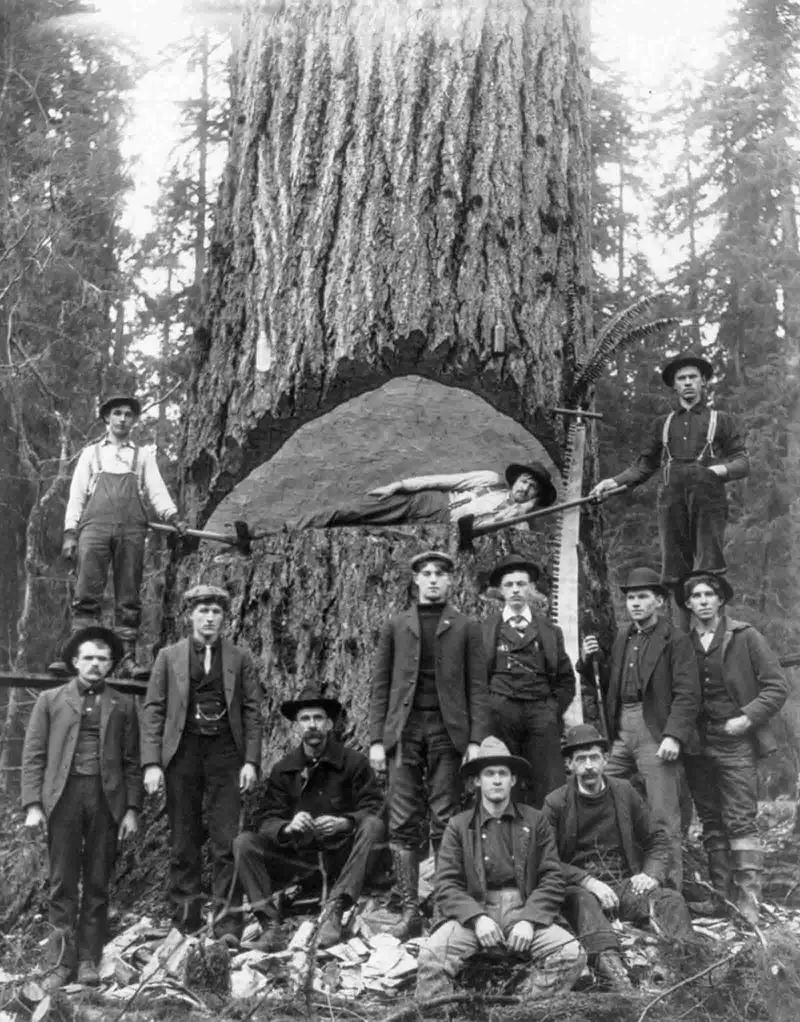

Lumberjacks pose with a Douglas fir tree in Washington. 1899.

Before the invention of motorized chainsaws and logging machinery, the hard work of felling trees was done by the lumberjacks using hand tools such as axes and saws.

The work was difficult, dangerous, intermittent, low-paying, and involved living in primitive conditions.

Lumberjacks worked in lumber camps and often lived a migratory life, following timber harvesting jobs as they opened.

They lived tightly packed in shanties (or bunkhouses) whose odor — a mix of smoke, sweat, and drying garments — was as distasteful as the bedbugs they supported.

Strict rules often governed many of the bush camps (or “shanties”); many were alcohol-free and for the longest time talking during meals was strictly forbidden.

Lumberjacks pose with a fir tree in Washington. 1902.

Lumberjacks could be found wherever there were vast forests to be harvested and a demand for wood, most likely in Scandinavia, Canada, and parts of the United States.

In the U.S., many lumberjacks were of Scandinavian ancestry, continuing the family tradition.

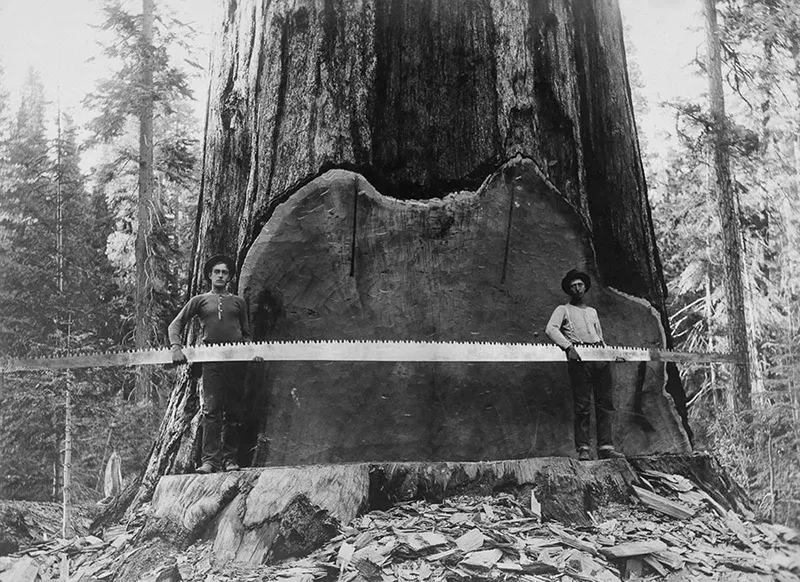

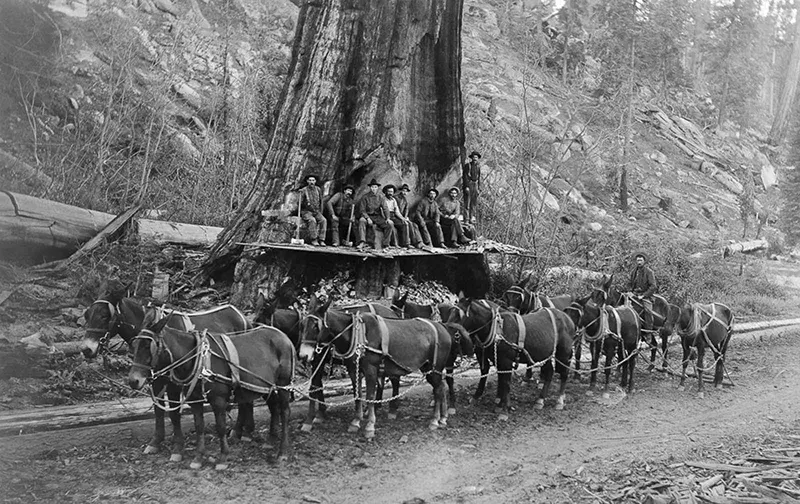

“Fallers” did the actual job of felling a tree with axes and cross-cut saws. Once felled and delimbed, a tree was either cut into logs by a “bucker,” or skidded or hauled to a railroad or river for transportation.

Typically, the loggers would stand on a springboard, which was slotted into notches in the tree above the base.

Using crosscut saws and axes, the loggers would then work on chopping a wedge into the tree. It was important to judge the direction of the cut for where the tree would fall.

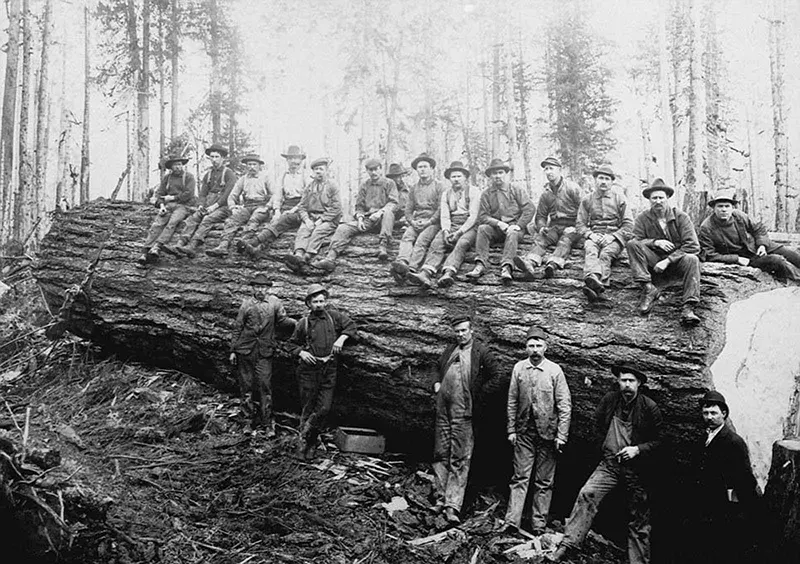

Lumberjacks pose with a 12-foot-wide fir tree. 1901.

The division of labor in lumber camps led to several specialized jobs on logging crews, such as whistle punk, chaser, and high climber.

The whistle punk’s job was to sound a whistle as a signal to the yarder operator controlling the movement of logs. He also had to act as a safety lookout.

A good whistle punk had to be alert and think fast as others’ safety depended on him.

The high climber (also known as a tree topper) used iron climbing hooks and rope to ascend a tall tree in the landing area of the logging site, where he would chop off limbs as he climbed, chop off the top of the tree, and finally attach pulleys and rigging to the tree.

After that, it could be used as a spar so logs could be skidded into the landing.

Three lumberjacks pose by a large Douglas fir ready for felling in Oregon. 1918.

The choker setters attached steel cables (or chokers) to downed logs so they could be dragged into the landing by the yarder. The chasers removed the chokers once the logs were at the landing.

Choker setters and chasers were often entry-level positions on logging crews, with more experienced loggers seeking to move up to more skill-intensive positions such as yarder operator and high climber or supervisory positions such as hook tender.

Despite the common perception that all loggers cut trees, the actual felling, and bucking of trees were also specialized job positions done by fallers and buckers.

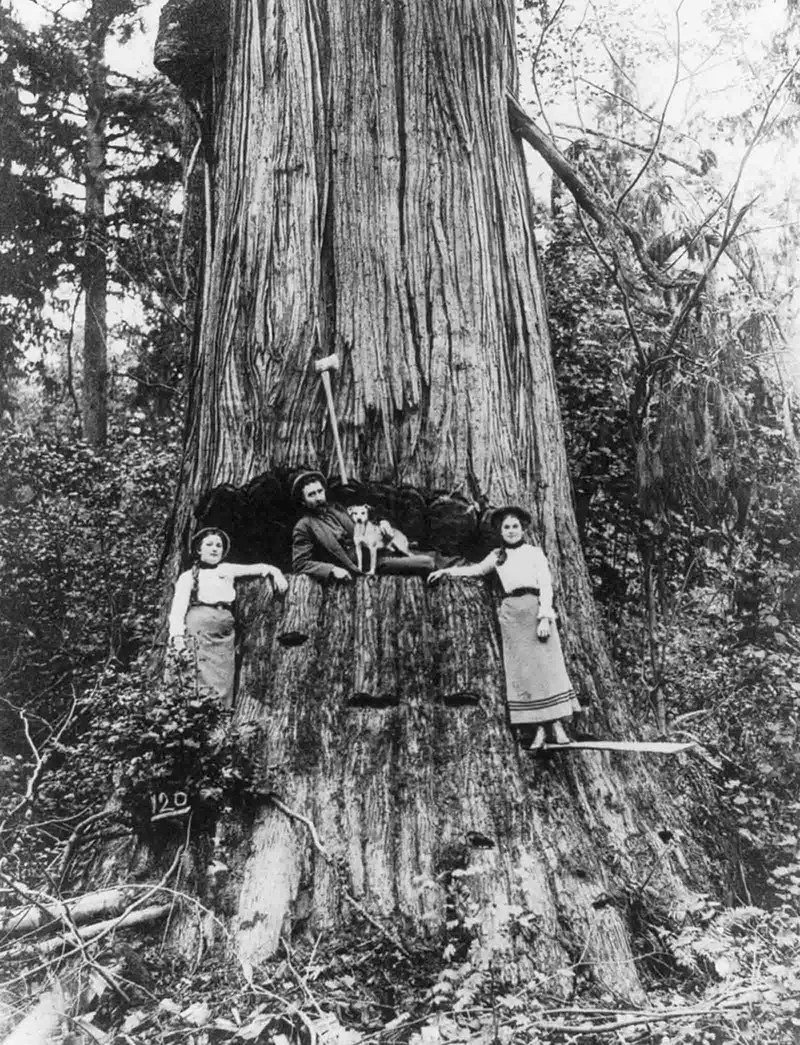

A lumberjack and two women pose in front of a tree near Seattle, Washington. 1905.

With the invention of motorized tools, vehicles, heavy machinery, and other powered tools, the profession and culture of the lumberjacks faded away.

Nowadays, lumber workers are known simply as loggers. In this article, we’ve collected vintage photos of lumberjacks from the turn of the last century as they looked to make their mark on America using only hand tools.

Loggers hold a cross-cut saw across a giant Sequoia tree’s trunk in California. 1917.

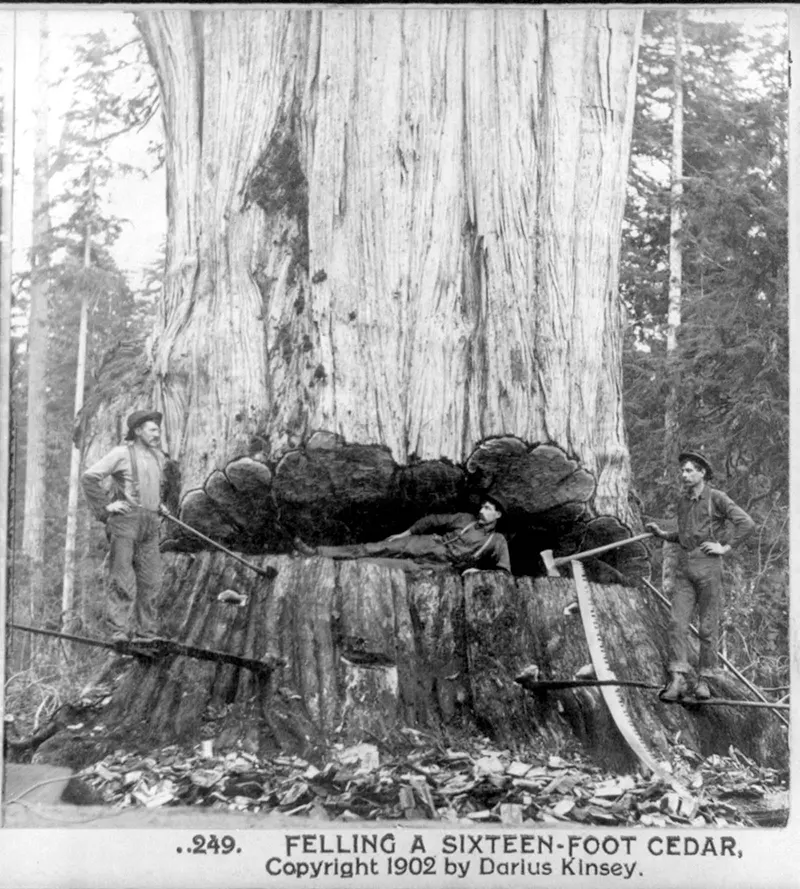

Lumberjacks undercut a giant sequoia tree in California. 1902.

Loggers and a 10-mule team prepare to fell a giant Sequoia tree in California. 1917.

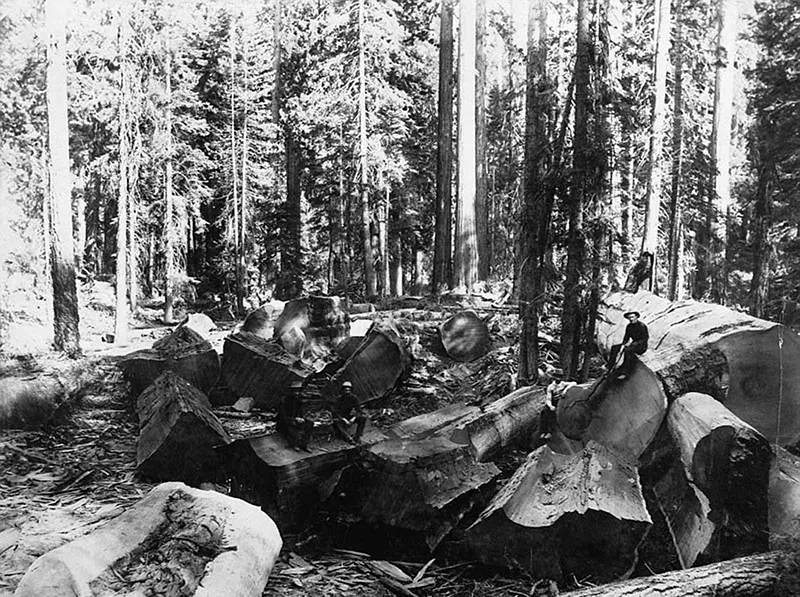

Loggers stand in the trunk of a tree they chopped down at Camp Badger in Tulare County, California. The tree was logged for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. 1892.

Lumberjacks pose on the stump of a tree which was displayed at St. Louis World’s Fair. 1904.

A logging crew stands among cut old growth longleaf pine in Vernon Parish, Louisiana. 1904.

Loggers walk the surface of a log jam on Minnesota’s Littlefork River seeking a tall, strong log with which to build a loading boom. 1937.

Men stand on piles of cut trees in rural New York. 1907.

Lumberjacks float lumber down the Columbia River in Oregon. 1910.

Over 100 people stand with a logged giant sequoia tree in California. 1917.

A lumberjack c. 1900.

Lumberjacks among the redwoods in California.

Lumberjacks in Washington state.

Standing by a Sequioa log in California, c. 1910.

A lumberjack stands on a felled spruce tree, c. 1918.

A lumberjack with a redwood.

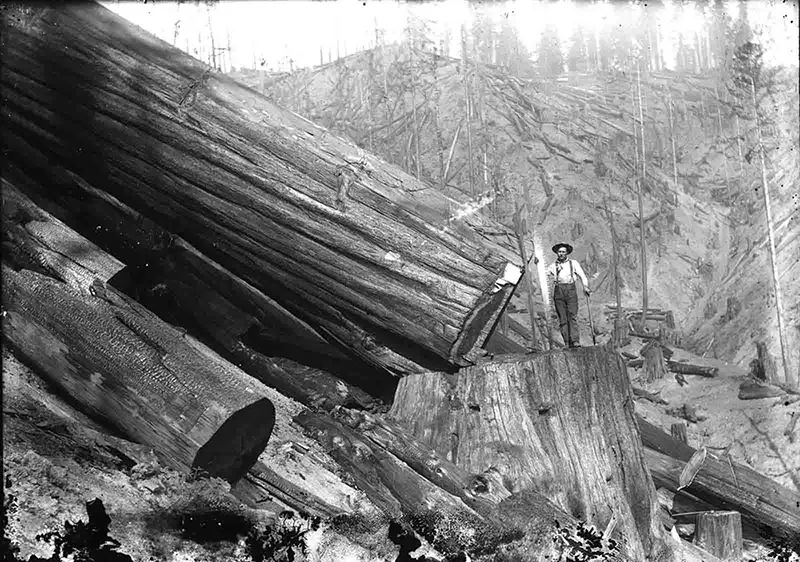

A felled Sequioa tree in California, c. 1900.

A lumberjack almost blends in with the cut trees.

A group in the 1930s moves a log into a river in West Virginia

The lumberjacks would often leave their families and live in camps where hundreds of their fellow workers relaxed between grueling shifts.

Lumberjacks sit on chunks of trees that they chopped down while looking around at the remaining forest surrounding them.

Three lumberjacks in 1900 stand next to a large fir log which has been cut using a sawing machine in Sedro-Woolley, Washington

Lumberjacks in Idaho clear a jam in the 1930s.

Several log rollers in the 1930s break up a log jam on the Little Fork River during the last log drive on that river in Koochiching County, Minnesota

A team of horses pulls a sled filled up with red and white pine logs in Red Lake County, Minnesota, at the beginning of the 20th century.

Horses were often the hardest workers on many of the logging camps, pulling trees such as these ones seen on a carrying vessel in 1890.

A crew stands among cut old growth longleaf pine near the settlement of Neame, now called Anacoco, in Vernon Parish, Louisiana.

Lumberjacks in Michigan load a series of white pine logs onto a train to be carried to a sawmill.

A crew in 1900 Washington state poses next to a donkey engine used for yarding logs, or gathering logs together after they are cut.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / National Geographic Creative / Corbis / U.S. Government Agriculture Forest Service).

Updated on: August 8, 2024

Any factual error or typo? Let us know.